Passover is perhaps the most universally familiar of the seven feasts of Moses, as many have seen the famous Cecil B. DeMille film, The Ten Commandments, which depicts the death of the firstborn, subsequently commemorated as Passover. When God called Moses in Exodus 4, He predicted that Pharaoh would not let the Hebrews go until the death of the firstborn. The movie, although a classic in many respects, makes it sound like the death of the firstborn was an afterthought or was attributed to Pharaoh’s defiance. But if you study the Scripture, you realize God hardened Pharaoh’s heart and told Moses that after a series of plagues He cast upon the Egyptians, it would be the death of the firstborn[1] that would finally convince Pharaoh to “let My people go!”[2]

In Exodus 11 and 12, God told Moses that the Hebrews were to take an unblemished lamb, keep it with them for four days and then kill it. Then they were to take the blood of that lamb and put it on the doorposts and the lintels of their house that particular night, which on the Hebrew calendar was the 14th of Nisan. And that very night the Death Angel passed through Egypt, and houses that had the blood on the doorposts and on the lintels were “passed over” by the Death Angel and the firstborns inside were spared.

The doors of the homes that were covered with blood were protected. If you were the firstborn of an Egyptian and just visiting a home with the lamb’s blood on the doorpost, you were spared. If you were a firstborn Hebrew and not in the house with the blood, you died. In other words, the discriminating element was the blood, not that they were Jewish or Israeli or Egyptian. Those who followed the instructions were “covered” by the blood and “passed over.” The key principle was to be covered by the blood. The Death Angel followed his instructions: if there was blood, he could pass over.

The firstborns of not just the Egyptian families, but of the cattle and everything else were taken that night. The trauma of that is unimaginable for us. We glibly talk about it and when we read the story in Exodus 11–13, we may think to ourselves, “Gee, that’s neat for Israel.” However, think about it from the perspective of the world empire. Remember, Egypt ruled the world at that time. It was a major empire and the firstborn throughout the land died mysteriously that night. What pain. What agony. What chaos on so many levels!

There’s also something interesting to consider. Passover was the 14th of Nisan, and the Jewish day begins at sundown. What day was it on the Egyptian calendar? The 13th because it’s a Gentile calendar: Friday the 13th. We are indebted to Emmanuel Velikovsky[3] for the research that uncovered this, but it is plausible that the tradition of an unlucky Friday the 13th may go back to the Gentile side of the Passover in Egypt. Interesting irony, and obviously from that day on, as they were instructed in Exodus 12, Jews have, throughout generations, observed this event called Passover, to commemorate the first Passover. Moses included his instructions from God concerning Passover in Exodus 12 and again in Leviticus 23.

Something that may not be obvious but is useful to recognize is that the nation of Israel is said to have been “born” that night. God speaks of Israel from that point on as His firstborn.[4] That is a label of position, not genealogy. That was when and where the Nation of Israel began.

Those of you who are prophecy buffs might be interested to know that the time in captivity in Egypt and the Exodus event was predicted 430 years earlier in God’s discussion with Abraham in Genesis 15:13–16. In fact, Arthur Pink in his commentary justifies the view that it was fulfilled to the very day.[5]

To understand Passover even more thoroughly one should understand the procedure. Passover is on the 14th of Nisan. Four days earlier on the 10th of Nisan, each family was to present their lamb for approval. It had to be without blemish. They also kept the lamb in their household for the four days. Picture keeping this innocent lamb in the household for four days. It becomes a pet, doesn’t it? And then on the 14th of Nisan they are to slaughter it for the observance of Passover. This sounds barbaric, doesn’t it? Yet God is making a point. He’s teaching them the same way He taught Adam and Eve in the Garden. Without the shedding of blood, there is no remission of sin.[6] Only by the shedding of innocent blood were they covered.[7] And it was an object lesson every year to the Jewish family that God does not wink at sin. It’s going to cost to have that covering. The sacrificed lamb was innocent and that lamb was slaughtered for the sins of the family.

From the 10th to the 14th, the lamb was under observation. On the 14th, “between the evenings,” it was to be slain. This is a very interesting phrase in the Torah, but it just describes the Hebrew day, which starts at sundown and goes to the next sundown. The entire lamb was to be consumed. Nothing was to be left until the next morning.[8]

Originally, the sacrifice was administered by the head of each household. Some scholars make the point that technically this is not a Levitical feast because sacrifices are normally the duty of the high priest. At that time, however, the High Priest approved the lamb and the head of the household dealt with the “sacrifice” for his household. Later, in Deuteronomy 16:2–7, the responsibility is transferred to the temple.

Christ our Passover

There are numerous items that tie the Passover to Jesus. It is not feasible to go into all of the details of the Passover in this study, but we can glean some highlights. Exodus 12 is a key chapter on the Lamb and in Exodus 12:46, the Scripture states that not a bone was to be broken. It’s repeated again in Numbers 9:12. It’s also predicted of the Messiah[9] that not a bone of His was to be broken.

Fast forward to Christ on the Cross. Crucifixion was a slow, painful death by suffocation. The outstretched arms, if you do a vector diagram, puts excruciating pressure on the chest cavity, causing suffocation. The only way to get air into the lungs is by putting upward pressure on the feet so you can relieve the tension. This is only done with great pain. The Persians invented crucifixion, but it was used by the Romans to be a very slow, conspicuous form of death as an example to those they were trying to dissuade from crime and from turning against the Roman Empire. Because of the holy day coming, it was necessary to remove Jesus’ body from the cross before the close of day. Therefore, they put out the order to break the legs of those who were crucified because that would hasten death. And you all know there was a Roman soldier who technically violated his orders. He saw that the man on the middle cross was already dead, but to make doubly sure, he thrust his sword into the side of Jesus.

How strange. Was that unnamed Roman soldier educated in the Torah? Did he know that Christ was our Passover? Was he a believer in the Messiah? Did he know that if he broke the bones, the model would have been broken? I doubt it, and yet how interesting it is that this unknowing gesture by this Roman soldier fulfilled prophecies that go back to the days of Moses.

Part of the Passover ritual is to go through the house and search for leaven to make sure the house is leaven-free. What is leaven? It is yeast that makes the bread rise and become soft and puffy. Passover is to be unleavened, because the Hebrew children had to leave Egypt so quickly there was no time for their bread to rise. We’ll talk more about leaven when we get into the Feast of Unleavened Bread, but this is another “type” of Jesus Christ. It’s interesting that to this day Jews participate in the bedikat chametz, where they search the house for leaven. To commemorate this, instead of just getting the leaven out of the house, they hide a little bit of it and the children get a prize if they can find it.

It’s interesting that here again you have the emphasis that the Passover Lamb is characterized by being unblemished and totally free of sin. You see the Messianic overtones here as well. It’s not only commemorative of what happened in Egypt (and that is the way it is emphasized in Judaism today), but it’s also predictive of the Messiah.

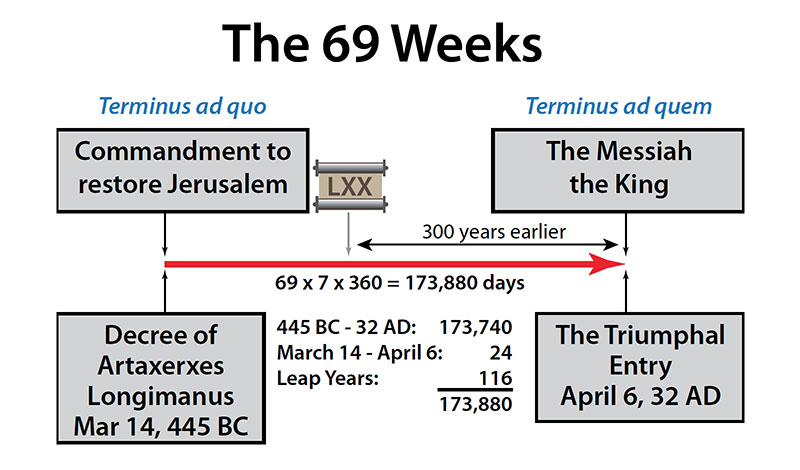

We noted earlier that the lamb was presented for observation on the 10th of Nisan, four days in advance of the sacrifice. By way of review, in Daniel 9 the angel Gabriel visits Daniel and gives him four verses, a mathematical prophecy.[10] I encourage those of you who are unfamiliar with these verses to study them thoroughly. As an aside, bear in mind the Old Testament was translated into Greek almost three centuries before Christ was born (the prophecy is so precise that critics claim it was written after Christ’s death). In Daniel 9 the angel Gabriel stated to Daniel that “from the going forth of the commandment to restore and rebuild Jerusalem unto the Meschiach Nagid, the Messiah the King, shall be seven weeks and threescore and two weeks.”[11] It was to be a very specific number of days. It happens to be 173,880 days.

There is only one time in the Bible when Jesus allowed Himself to be worshiped as a king. Several times during His ministry, the soldiers try to take Him and He says “My time is not yet come, or My hour is not yet come.” Then one day He not only permits it, He arranges it and, in order to fulfill Zechariah 9:9, He rides into Jerusalem on a donkey. We celebrate this day on what we refer to as Palm Sunday or the Triumphal Entry.

Jesus rides into Jerusalem, but He also weeps over the city because He realized they didn’t recognize who He really was. And He says, “Because you did not recognize this thy day, these things are now hidden.”[12] Forever? No, there is a day when they’ll be revealed. Paul tells us in Romans 11:25 when that will be. The point is that as we study history, we know when the decree was[13] and we know the date of His entry[14] and the interval is exactly 173,880 days.

In other words, the day that Jesus rode the donkey into Jerusalem is the 10th of Nisan (Jewish calendar), the same day that over in the temple area they were reviewing the lambs that were presented. Jesus was presenting Himself to Israel as The Lamb on the very day that Gabriel predicted five centuries earlier.[15] God says what He means and means what He says.

For as much as ye know that you were not redeemed with corruptible things, like silver and gold from your vain manner of life received by the tradition of your fathers, but with the precious blood of Christ as of a lamb without blemish and without spot who verily was foreordained before the foundation of the world but was manifest in these last times for you…

— 1 Peter 1:18–21

Peter clearly has in his mind the fulfillment of the Passover Lamb by Jesus Christ, who was without spot or blemish. When John the Baptist first introduces Jesus he says “Behold, the Lamb of God that taketh away the sins of the world.”[16] Paul equates Jesus with the Passover in 1 Corinthians 5:7, “For indeed, Christ, our Passover, was sacrificed for us.” He was found without blemish, not a bone was broken. Pontius Pilate even said, “I find no fault in Him.”[17]

In Exodus 12, there seems to be a strange contradiction:

Your lamb shall be without blemish. A male of the first year. Ye shall take it out from the sheep or from the goats and ye shall keep it until the fourteenth day of the same month and the whole assembly of the congregation of Israel shall kill it in the evening.

— Exodus 12:5

It’s a strange grammatical construction because as you continue in Chapter 12, you will discover there’s one for each family, just like they did the night of the Exodus. But if you read the grammar carefully, it’s as if there’s only one lamb: “You shall kill it for the whole congregation.”

The implication is that there is one “lamb” for everyone. That was not the case at the time of the Exodus. There was one lamb for each household. Do you see a hint of things to come?

Not only is Jesus presented as the Passover in general, but even the specific aspects of the feast point to Him. When the LORD God describes the forthcoming Passover, He says to Moses:

Therefore say unto the children of Israel, I am the Lord, and I will bring you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians. I will rid you out of your bondage. I will redeem you with an outstretched arm and with great judgments. And I will take you to me for a people, and I will be to you a God; and ye shall know that I am the Lord your God, which bringeth you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians.

— Exodus 6:6–7

From this quote, the Jews highlight four major commands:

- I will bring you out

- I will rid you out of your bondage

- I will redeem you with an outstretched arm

- I will take you to Me for a people

From these four commands, the Jews label the four cups used in the Passover presentation:

The first is the Cup of Consecration (I will bring you out). The second is the Cup of Deliverance (I will rid you out of your bondage — “I will take Egypt out of you”). The third is the Cup of Passover (the Cup of Redemption, which Paul also calls “the Cup of Blessing”). The fourth cup is “I Will Take You as a People” (which commemorates God taking Israel to be His people).

Jesus uses the Cup of Redemption to institute the Last Supper or the Last Seder, as Paul highlights in 1 Corinthians 10:16 and 11:23ff. Notice that He does not lift the fourth cup. Instead, He takes a Nazarene vow saying, “I will not drink henceforth of this fruit of the vine, until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom.”[18]

That’s the cup that symbolizes, “I will take you to be My People.” Christ will lift us up from the world through Redemption, to be His people, to be with Him in the Kingdom of God when He presents His Bride to God the Father.

As we mentioned earlier, “The New Testament is in the Old Testament concealed; The Old Testament is in the New Testament revealed.” You will discover as you delve deeper into your Bible that the Old Testament anticipates the New Testament. If you want to take Passover seriously, I encourage you to study Isaiah 53 and Psalm 22.

Actually, Isaiah 53 begins about three verses earlier with the last three verses of chapter 52. Those three verses, Isaiah 52:13–15 and Isaiah 53 describe the mission of Jesus Christ during His First Coming that’s just as vivid as if you digested all of the Pauline epistles. The substitutionary death of the Messiah on our behalf is so explicit in Isaiah 53 that the Sephardic Jews removed it from their Scriptures. The Ashkenazi Jews kept it.[19] In 1947, when the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, they found a complete scroll of Isaiah, created by the Essenes more than a century before Jesus’ birth. You can go to Israel to the Shrine of the Book and look at this magnificent scroll. Right in the middle of Isaiah is, guess what? Isaiah 53.

The other amazing passage is Psalm 22, especially the last half of it. It’s very vivid. As you read it, you will be gripped by the reality that it reads as if it were written in the first person singular by Jesus as He hung on the cross. As He hears the people mock Him. As He looks down and watches the soldiers cast lots for His vesture. How He takes vinegar to drink and how His hands and feet are pierced. Amazing! In fact, Jesus calls your attention to Psalm 22 when He cries out, “Eli, Eli, Lama Sabachthani”[20] from the cross.[21] He quotes the first verse of Psalm 22. His last words on the cross are implied and summarized in the last verse of Psalm 22: “It is done. It is finished.”

One of the most interesting things you can do when given the opportunity is to attend a Jewish Seder, especially one given by a Messianic Jew. But it may in fact be more valid if you go to an Orthodox Jewish Seder because it will not be bent or tailored for you. It will be straight from the Jewish tradition.

You’ll notice they have the matzah, the unleavened bread, and it is both pierced and striped. Think about it and then read again Isaiah 53, especially Isaiah 53:5. There are always three pieces of bread and the middle one is always broken. Half of it is wrapped in a cloth and hidden between the other two. When you ask “why?” many are unsure. Even the rabbis argue about it and yet from the New Testament perspective we have additional insights:

Then were there two thieves crucified with him, one on the right hand, and another on the left.

— Matthew 27:38

And when Joseph had taken the body, he wrapped it in a clean linen cloth, and laid it in his own new tomb, which he had hewn out in the rock: and he rolled a great stone to the door of the sepulcher, and departed.

— Matthew 27:59–60

The shedding of the Passover Lamb’s blood is the key issue of the Passover. It commemorates the blood on the doorposts, but it also commemorates the whole concept of blood redemption on which the whole entire Torah is based, as is your redemption and mine.

…and I have given it to you upon the altar to make atonement for your souls; for it is the blood that makes atonement for the soul.

— Leviticus 17:11

The same message is echoed in Hebrews 9:22b, “Without the shedding of blood, there is no remission.” The Jews are very anxious to have their Temple rebuilt because they need the Temple in order to have an altar. They need the altar to shed the blood to make these laws operative. Right now they have had centuries of an elaborate rationalization using works rather than really obeying the literal Law and making a blood sacrifice. Matthew 26:28 records the words of Jesus for us. “Take, drink, this is my blood shed for you.” It’s anticipatory of what’s going to happen before the day is over.

John 19:34 is a provocative verse. In the Mishnah[22] in 7, Verse 13, it mentions that when they administer the wine during the Passover meal, it is supposed to be mixed with warm water. And you can search the literature and various rabbis have different conjectures as to what this signifies and why they do it, but they don’t really know why. They only know you are supposed to do it. In John 19:34, when the Roman soldier thrusts his spear into the Lord’s side, what comes out? Blood and water. And what was the water temperature? Warm. How interesting.

The Passover guide or script is called the Haggadah. Exodus 13:8 says, “And you shall tell your son in that day, saying, ‘This is done because of what the Lord did for me when I came up from Egypt.’” In Hebrew, Haggadah means “the showing forth.” Paul in his description of the Last Supper says, “For as often as ye eat this bread, and drink this cup, ye do show the Lord’s death till He come.”[23] It’s a prophetic term. During the season of Passover, examine your personal relationship with Jesus Christ. I urge you to apply the blood of our Passover Lamb to your heart.[24]

Notes:

- Exodus 4:23 ↩

- Exodus 9:1 ↩

- Velikovsky, Immanuel. Worlds in Collision. New York: Macmillan Publishers, 1950, pp. 62–65. “This happened on the night of the 14th of the month of Aviv. (Exodus 12:6 and 13:4) This is the night of Passover, as the Israelites originally celebrated Passover on the eve of the 14th of Aviv. (Where) the Hebrews counted, and still count, the beginning of the day from sunset, the Egyptians reckoned from sunrise. For the Egyptians it was the 13th day. Here we have the answer to the open question concerning the origin of the superstition which regards the number 13, and especially the 13th day, as unlucky and inauspicious. (There is no) record of this belief found dating from before the Exodus. ↩

- Exodus 4:22 ↩

- Pink, Arthur. Gleanings in Genesis. Digireads.com, 2005, Chapter 20, Genesis 15:13–16. Abraham’s Vision, p. 98ff. “And He said unto Abram, know of a surety that thy seed shall be a stranger in a land that is not theirs, and shall serve them; and they shall afflict them four hundred years. And also that nation, whom they shall serve, will I judge; and afterward shall they come out with great substance. And thou shalt go to thy fathers in peace; thou shalt be buried in a good old age. But in the fourth generation they shall come hither again; for the iniquity of the Amorites is not yet full” (vv. 13–16). These verses contain a sevenfold prophecy which received a literal and complete fulfillment. It had reference to the sojourn of Abram’s descendants in the land of Egypt, their bondage there, and their deliverance and return to Canaan. We can do little more now than outline the divisions of this compound prophecy. First, Abram’s descendants were to be strangers in a land not theirs (v. 13). Second, in that strange land they were to “serve” (v. 13). Third, they were to be “afflicted” four hundred years (v. 13)—note that Exodus 12:40 views the entire “sojourning” of the children of Israel in Egypt. They “dwelt” in Egypt four hundred and thirty years, but were “afflicted” for only four hundred years of that time. ↩

- Hebrews 9:22 ↩

- Genesis 3:21 ↩

- Exodus 12:1–13; Leviticus 23:4–5 ↩

- Psalm 34:20 ↩

- Missler, Chuck. Cosmic Codes. Koinonia House: Post Falls, ID. Chart, p. 237. ↩

- Daniel 9:25 ↩

- Luke 19:44 ↩

- Decree of Artaxerxes Longimanus on March 14, 445 BC ↩

- The Triumphal Entry, on April 6, 32 AD or Nisan 10 ↩

- Missler, Chuck. Cosmic Codes. Koinonia House: Post Falls, ID. Chart, p. 237. ↩

- John 1:29 ↩

- Luke 23:4; John 18:38; 19:4; 19:6 ↩

- Matthew 26:27–29 ↩

- Sephardic Jews are from Spain, Portugal, North Africa and the Middle East. They are more liberal in their interpretation of the Law than the Ashkenazic Jews, who are primarily from France, Germany and Eastern Europe. Yiddish is the language of Ashkenazic Jews, and based on German and Hebrew. The Sephardic Jews have their language, Ladino, based on Spanish and Hebrew. ↩

- Psalm 22:1 ↩

- Matthew 27:45 ↩

- The Mishnah is the first section of the Talmud, being a collection of early oral interpretations of the Scriptures as compiled about 200 AD. ↩

- 1 Corinthians 11:26 ↩

- 1 John 1:7; 1 Corinthians 15:51; Ephesians 2:13; John 5:24 ↩